Text by JONAS BERTHOD

Collaboration

Geometries

of collaboration

In popular culture, the creative process is often depicted as a lonely endeavour. But while a bereft, misunderstood genius producing a masterpiece through tears and sweat is indeed a compelling narrative, the image could not be further from reality.Harrison C. White and Cynthia A. White, “Canvases and Careers”, New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1965. To paraphrase Becker’s argument in Art Worlds, the designer, photographer or mediator — who we should really think of as any other type of worker — relies on extensive networks to produce the kind of labour that the applied arts world is noted for.Howard S. Becker, “Art Worlds”, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982. Whether it is to share knowledge, produce work, distribute the result of the effort or let an audience appraise it, cooperation is paramount to creation.

Needless to say, the Swiss Design Awards play a significant role in this network. They have done so for more than a century. They engage in the world of applied arts by encouraging the field through financial support, commissioning designers and promoting them. For the nominees, however, other synergies happen earlier. The most fundamental advantage of teaming up with others is that it lets us connect different skills to create work that goes further than what is achievable by a single person. This teamwork takes place at different levels, starting with joint efforts in the atelier and ranging to external cooperation with partners, suppliers and clients. How does working together impact the creative process of this year’s nominees? How do they organise to combine efforts, and what are the different qualities of collaboration?

Dans la culture populaire, le processus créatif est souvent dépeint comme un effort solitaire. Admettons-le : l’image d’un génie désespéré, incompris de tous, produisant un chef-d’œuvre à force de larmes et de sueur nous offre un potentiel narratif sans équivalent. Mais cette image ne pourrait être plus éloignée de la réalité.Harrison C. White et Cynthia A. White, « Canvases and Careers », New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1965. Pour paraphraser l’argument avancé par Becker dans Art Worlds, les métiers de designer, photographe ou médiateur – qu’on ne devrait en réalité pas envisager différemment d’autres professions – dépendent de réseaux étendus pour créer le genre de travail pour lequel le monde des arts appliqués est reconnu.Howard S. Becker, « Art Worlds », Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982. Qu’il s’agisse de partager un savoir, produire des travaux, distribuer le résultat de l’effort ou permettre à une audience de l’évaluer, la coopération est d’une importance capitale pour la création.

Les Prix suisses de design jouent un rôle considérable dans ce réseau. Ils le font depuis plus d’un siècle, prenant part au monde des arts appliqués en l’encourageant par des soutiens financiers, par la promotion de designers et l’octroi de mandats. En ce qui concerne les nominé·e·s, d’autres synergies prennent place plus tôt dans le processus. L’avantage fondamental de la collaboration, c’est qu’elle permet de connecter différentes compétences pour créer des projets qui vont plus loin que ce qu’une personne seule pourrait accomplir. Ces partenariats prennent place à différents niveaux : d’abord au sein de l’atelier, puis dans la coopération externe avec des partenaires, fournisseurs et clients. Quel impact ont ces associations sur le processus créatif des nominé·e·s cette année ? Comment s’organisent-elles et ils pour combiner leurs efforts avec d’autres, et quelles sont les différentes qualités de la collaboration ?

In its most straightforward appearance, collaboration is internal and takes place between designers within the same sphere of practice. We could schematize it by parallel lines: practitioners combine similar and often completing skills. Product designers Micael Filipe and Romain Viricel, who met at ECAL, chose to have equal roles in the design process. They both possess a similar skill set, so the particularity each person brings to the collaboration is their personal experience, taste and way of looking. Now based in London for the former and Lyon for the latter, they are nominated for the Midi Chair, which they developed over a year of almost daily conversation. And how did they share ideas? Their medium of choice is the failproof sketch, albeit in a contemporary form. “We use drawings or 3D renders as supports to share an idea; a good drawing doesn’t necessarily need an explanation. We also meet regularly in person to materialise our ideas through a physical model.”

Sous son apparence la plus simple, la collaboration est interne. Elle prend place entre des designers au sein d’une même sphère d’activité. On pourrait la schématiser par des lignes parallèles : les designers combinent des compétences similaires et souvent complémentaires. Les designers de produit Micael Filipe et Romain Viricel, qui se sont rencontrés à l’ECAL, ont choisi d’avoir des rôles égaux dans le processus de création. Les deux possèdent des aptitudes similaires. En conséquence, les spécificités que chacun apporte à l’entreprise sont leurs regards, leurs goûts et leurs expériences individuelles. Aujourd’hui, Filipe habite à Londres et Viricel, à Lyon. Ils présentent cette année la Midi Chair, une pièce qu’ils ont développée au long d’une année de conversations presque quotidiennes. Et comment partagent-ils leurs idées ? Leur support de choix est le dessin, un moyen infaillible qu’ils mettent au goût du jour. « Le dessin ou la 3D sont d’excellents supports pour poser une idée. Un bon dessin n’a pas forcément besoin d’une légende. Régulièrement, nous nous rejoignons à Londres ou à Lyon. Cette rencontre est le moment lors duquel nos recherches se matérialisent par une maquette. »

“A good drawing doesn’t necessarily need an explanation.”

« Un bon dessin n’a pas forcément besoin d’une légende. »

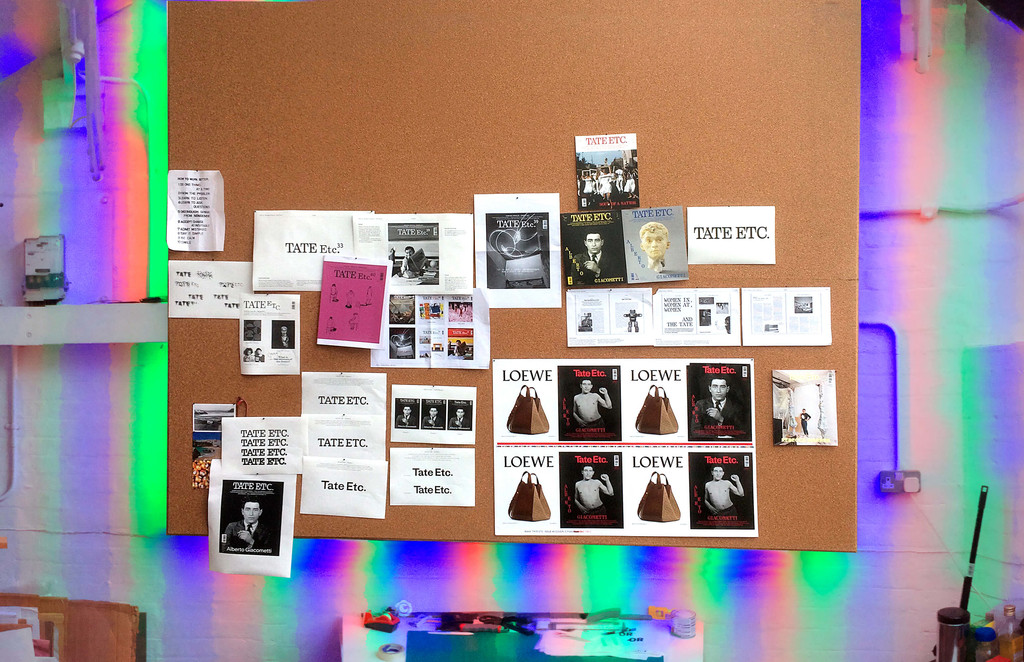

Graphic design Studio Ard (Guillaume Chuard and Daniel Nørregaard) use a slow, organic collaborative process that also depends on visual material: a giant pinboard that acts as the receptacle for inchoate ideas. Rather than take decisions, they rely on an informal process where they stimulate each other through references and tests. At some point, one designer naturally takes responsibility for the project. The duo met at the Royal College of Art in London after studying at ECAL and the Gerrit Rietveld Academie and see their practice at the centre of a triangle defined by Swiss rationality, Dutch radicalism and English pop. To this smorgasbord of influences, they add their own preferences: Chuard is passionate about materiality while Nørregaard is enthusiastic about texts. When it comes to choosing the music in the studio, each has his taste too — though Nørregaard has the upper hand as he often arrives before Chuard in the morning. The real struggle of working together so closely begins at noon. Chuard cannot eat gluten and Nørregaard is a lactose-intolerant vegetarian, making lunch the most difficult decision of the day.

Le Studio Ard (formé par les designers graphiques Guillaume Chuard et Daniel Nørregaard) utilise un processus collaboratif organique qui repose lui aussi sur du matériel visuel : un tableau d’affichage géant qui sert de réceptacle pour les idées au fur et à mesure qu’elles s’ébauchent. Au lieu de de prendre des décisions, ils comptent sur un processus informel où chacun stimule l’autre à l’aide de références et de tests. A un certain moment, l’un des deux prend naturellement la responsabilité d’un projet donné. Le duo, qui a fait connaissance au Royal College of Art à Londres après des études à l’ECAL et à la Gerrit Rietveld Academie, voit sa pratique au centre d’un triangle défini par la rationalité suisse, le radicalisme néerlandais et la pop anglaise. A cette panoplie d’influences s’ajoutent leurs propres préférences : Chuard est passionné par la matérialité tandis que Nørregaard est fasciné par le texte. Quand il s’agit de choisir la musique dans le studio, chacun a également ses goûts – mais Nørregaard a le dernier mot, puisqu’il arrive souvent avant Chuard le matin. La vraie difficulté, quand on travaille ensemble de manière si rapprochée commence à midi. Chuard ne peut pas manger de gluten, tandis que Nørregaard est un végétarien intolérant au lactose, ce qui rend le choix du déjeuner la décision la plus difficile de la journée.

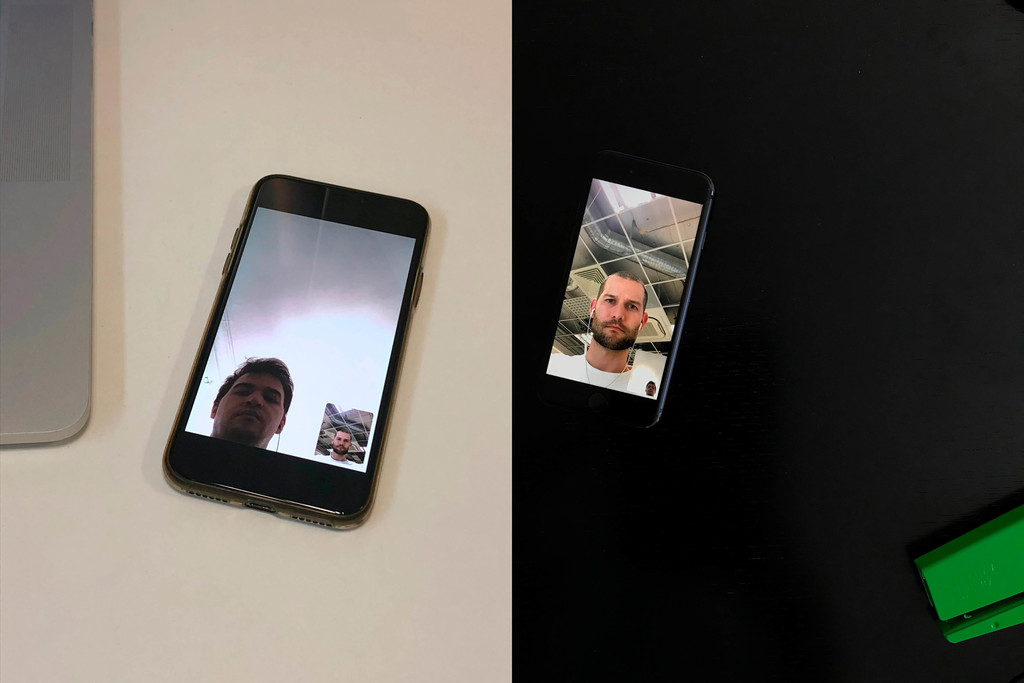

But other designers never have the opportunity to break bread: they collaborate across different locations and must, therefore, rely on other systems to share ideas. The duo of graphic designers No Plans (Daniel Pianetti in New York and Daniel Baer in London) attempted splitting web design jobs at first, with one partner taking care of the design and the other coding it. However, they realised that they worked best when each took turns leading specific projects, with the other person having the role of critiquing it regularly. “We have surprisingly different personalities and design styles. We both understand and respect the other’s approach to visual design and interfaces. Interestingly, we could never replicate what the other half is doing.” With one designer in New York and the other in London, collaboration takes place across many digital platforms (Trello, Appear.in, Slack, GitHub, Google Suite and so on) to ensure constant communication.

Mais d’autres designers n’ont jamais l’occasion de rompre le pain ensemble : ils collaborent à partir d’endroits différents et dépendent donc d’autres systèmes pour partager leurs idées. Au début, les designers graphiques No Plans (Daniel Pianetti à New York et Daniel Baer à Londres) ont tenté de diviser leurs mandats de web design, l’un s’occupant du design et l’autre du code. Ils ont toutefois rapidement compris qu’ils travaillent mieux quand chacun prend la direction d’un projet à son tour, l’autre personne jouant régulièrement le rôle de critique. « Nous avons des personnalités et des styles étonnamment différents. Nous comprenons et respectons l’approche de l’autre en ce qui concerne le design visuel et d’interfaces. Chose intéressante, on ne pourrait jamais répliquer ce que l’autre moitié fait. » Avec un designer à New York et l’autre à Londres, la collaboration prend place sur plusieurs plateformes digitales (Trello, Appear.in, Slack, GitHub et Google Suite parmi d’autres) pour permettre de rester en contact constant.

“We could never replicate what the other half is doing.”

« On ne pourrait jamais répliquer ce que l’autre moitié fait. »

But there's another, less corporate platform which plays a significant role for No Plans. Daniel Pianetti is one of the founders of Are.na, the collaborative tool for visual organisation. For the duo, the platform is more than a means to share ideas internally. “Are.na has a special role in our projects due to its community: as we collaborate over time with other designers, developers and clients, these connections become a resource themselves. It’s not rare to pick a collaborator’s contribution for a completely unrelated project months later, ask an old client about an event they’re researching for on the platform and enquire or even be asked for services after diving into someone’s online research.” By creating their own collaborative tool, the designers bring together online and offline communities. Furthermore, they have access to flexible partnerships. This contributes to redefining the idea of the collective.

Mais il y a une autre plateforme, moins commerciale, qui joue un rôle considérable pour No Plans. Daniel Pianetti est l’un des membres fondateurs de Are.na, un outil collaboratif qui permet d’organiser des références de manière visuelle. Pour le duo, la plateforme n’est pas qu’un moyen de partager des idées à l’interne. « Are.na joue un rôle particulier dans nos projets à cause de sa communauté. Au fur et à mesure que nous collaborons avec d’autres designers, développeurs et clients, ces connections deviennent elle-même des ressources. Il n’est pas rare, des mois plus tard, de choisir la contribution d’un collaborateur pour un projet sans aucun rapport, de s’informer auprès d’un ancien client sur un événement qu’ils sont en train d’organiser à l’aide de références sur la plateforme, ou de se renseigner voire d’être consultés pour des services après avoir plongé dans la recherche de quelqu’un d’autre. » En créant leur propre outil collaboratif, les designers rassemblent des communautés en et hors ligne. Par ailleurs, ils ont accès à des partenariats flexibles. Cela contribue à redéfinir l’idée même du collectif.

Fashion designers Collective Swallow (Anaïs Marti and Ugo Pecoraio, who met at FNHW Basel) are also based in two different locations, Basel and Berlin. The first half of their moniker is a nod to the fact that creating a collection is always a joint effort. “There are so many more people involved than just the two of us, and we like to collaborate with other designers or artists for specific products.” Within the collective itself, each plays a specific role which evolved over time and comes from their education but also reflects group dynamics. Marti has a background in tailoring and experience as a commercial fashion designer. She is therefore in charge of developing the collection, creating the pieces and managing the production.

Les créateurs de mode Collective Swallow (Anaïs Marti et Ugo Pecoraio, qui se sont rencontrés à la FNHW Bâle) sont aussi basés dans deux villes différentes, Bâle et Berlin. La première moitié de leur nom est clin d’œil au fait que la création d’une collection est toujours un effort conjoint. « Il y a tellement plus de personnes qui sont impliquées que juste nous deux, et nous aimons collaborer avec d’autres designers ou artistes sur des produits spécifiques. » Au sein du collectif, chaque membre joue un rôle spécifique qui a évolué avec le temps et provient de leur éducation, mais reflète aussi les dynamiques du groupe. Marti a une formation de tailleur et de l’expérience comme designer de mode commerciale. Elle est donc responsable du développement de la collection, de la création des pièces et de la gestion de la production.

On the other hand, Pecoraio has experience in the PR world. His background in graphic design means he also oversees prints, look-books, labels and hangtags. “We both have our areas of expertise but working closely together is very important. In the beginning of a collection, we both research and collect inputs which we then select and structure together. We meet for a weekend in a house in the Jura and discuss and shape the new upcoming collection. There, we create the mood board and finalise the concept which then leads all following actions to the collection.” After this process, Marti takes over: she draws and develops the pieces. Along the way, there is a delicate balance between shared decisions and relying on each other’s expertise, an equilibrium which is nurtured by their relationship. Indeed, Collective Swallow stresses that their collaboration stems from friendship: “we were friends first, and then decided to build a label together.”

D’un autre côté, Pecoraio a de l’expérience dans le monde des relations publiques. Grâce à sa formation en design graphique, il supervise imprimés, lookbooks et étiquettes. « Nous avons chacun nos domaines de compétence, mais une collaboration rapprochée est très importante. Au début de chaque collection, nous faisons les deux des recherches et collectionnons des références que nous sélectionnons et structurons ensuite. Nous nous rencontrons pendant un weekend dans une maison dans le Jura pour discuter et former la nouvelle collection. A ce moment-là, nous créons le moodboard et finalisons le concept qui dirige ensuite toutes les actions qui formeront la collection. » Après ce processus, Marti prend les devants : elle dessine puis développe les pièces. Au fil du chemin, un équilibre délicat s’établit entre décisions partagées et l’expertise de chacun, une balance nourrie par leur relation. En effet, Collective Swallow souligne que leur collaboration provient avant tout de leur amitié : « nous étions d’abord amis, et avons décidé ensuite de construire une marque ensemble. »

“We were friends first, and then decided to build a label together.”

In a slightly different example of teamwork, nominees group together for projects which take place outside of their usual field. In these cases, collaborating is about creating perpendicular bisectors. Denis Roueche, who trained as a graphic designer, and Prune Simon-Vermot, who studied photography, teamed up to open Palais—Galerie. Quite naturally, each brought their skills to the table: Roueche designs the posters and Simon-Vermot documents the exhibitions. But the main work of a gallery — curation, which goes beyond their initial training — is shared by both equally; teamwork truly makes the dream… work.

Another example would be Agathe Zaerpour and Philippine Chaumont. They trained as graphic designers together at ECAL and increasingly worked as art directors after graduating. So far, their trajectory is not unusual. This year, however, they are applying in the photography category with projects spanning from the documentary to the self-initiated and the editorial. Their work mirrors the skills they have in the fields of both design and photography. By teaming up together, they are in a position to develop a photographic discourse that is firmly their own. Not only does it display a graphic approach — both in the composition of the images and their presentation in rhythmic layouts — but it also delivers their own voice: a self-confident, uncanny quirkiness that seeps through the subjects they choose and the treatment of their images.

Dans certains exemples de travail d’équipe, les nominé·e·s se regroupent pour des projets qui prennent place en-dehors de leur champ habituel. Dans ces cas, la collaboration crée des bissectrices perpendiculaires. Denis Roueche, qui a une formation de designer graphique, et Prune Simon-Vermot, qui a étudié la photographie, ont joint leurs forces pour ouvrir Palais—Galerie. Assez naturellement, chacun apporte ses compétences : Roueche conçoit les posters tandis que Vermot documente les expositions. Mais le travail principal d’une galerie – la curation, une pratique qui se situe au-delà de leur formation originelle – est partagé par les deux de manière équivalente. Le travail d’équipe rend le rêve possible.

Un autre exemple serait le travail d’Agathe Zaerpour et Philippine Chaumont. Elles ont étudié le design graphique ensemble à l’ECAL et, une fois leur diplôme en poche, ont travaillé de plus en plus en tant que directrices artistiques. Jusque-là, rien d’inhabituel dans ce type de trajectoire. Cette année, cependant, elles présentent leur travail dans la catégorie photographie avec des projets qui vont du travail documentaire à l’auto-initié, en passant par l’éditorial. Leur travail reflète les aptitudes qu’elles possèdent tant dans le champ du design que dans celui de la photographie. En travaillant ensemble, elles sont dans une position qui leur permet de développer un discours photographique qui est fermement le leur. Il fait non seulement démonstration d’une approche graphique – tant dans la composition des images que dans leur présentation en séquences rythmées – mais communique également leur voix personnelle : une excentricité troublante et assumée qui s’exprime aussi bien dans les sujets qu’elles choisissent que dans le traitement de leurs images.

By teaming up together, they develop a photographic discourse that is firmly their own.

En travaillant ensemble, elles développent un discours photographique qui est fermement le leur.

When nominees work hand in hand with clients, the partnership becomes a new space where the work can develop thanks to the convergence of needs and wants from all sides. We could schematise it by the intersection between different planes. Even further, collaboration can lead to practices that exist in the liminal space between various fields. For instance, photographer Marc Asekhame is also the publisher of a magazine, Periodico, which he edits in collaboration with graphic designer Teo Schifferli. When he is working on Periodico, Asekhame is therefore simultaneously photographer, editor, publisher and agent.

He blurs the line further by shooting personalised advertisements in close collaboration with the announcers, consequently benefitting thrice from the partnership: it brings financial support, lets him work as a photographer and hands him complete creative control over the magazine. Asekhame says: “I understand the ads in Periodico as an integral part of the content of the magazine. They become a collaboration between the institution/the brand and the publication.” But the periodical might well have the upper hand in this partnership, thanks to the clear conditions it sets. “For the last two issues, we let the advertiser appoint one person who would be portrayed by us and then, with the addition of the logo, become the advertisement.” Until now, this strategy has been successful and even seems to be convincing new clients. “So far, we have mostly worked with people who knew the magazine or my work, but now people approach us to publish and collaborate on an ad.” For a brand or institution, commissioning an ad thus becomes a way to borrow the magazine’s voice and present themselves as true partners to a cultural enterprise.

Quand les nominé·e·s travaillent main dans la main avec leurs clients, le partenariat devient un espace où les projets peuvent se développer grâce à la convergence entre les besoins et les désirs de chaque côté. On pourrait représenter cette situation par l’intersection de différents plans. Plus encore, la collaboration peut permettre à des pratiques d’exister dans l’espace liminal entre différents domaines. Par exemple, le photographe Marc Asekhame publie également un magazine Periodico, qu’il édite en collaboration avec le designer graphique Teo Schifferli. Quand il travaille sur Periodico, Asekhame est donc à la fois photographe, rédacteur, éditeur et agent.

Asekhame estompe encore plus la distinction entre ces champs lorsqu’il photographie des publicités personnalisées en collaboration avec les annonceurs du magazine. Ce faisant, il bénéficie triplement du partenariat : ce dernier lui apporte un soutien financier, lui permet de travailler en tant que photographe et lui donne un contrôle créatif complet sur le magazine. Asekhame explique qu’il voit les publicités dans Periodico « comme une partie intégrale du contenu du magazine. Elles deviennent une collaboration entre une institution ou une marque et la publication. » Mais le magazine pourrait bien avoir le dessus dans ce partenariat, grâce aux conditions qu’il pose. « Pour les deux derniers numéros, nous avons permis à l’annonceur de choisir une personne qui serait ensuite photographiée par nous et, après ajout d’un logo, deviendrait la publicité. » La stratégie a été un succès et a même l’air de convaincre de nouveaux clients. « Jusqu’ici, on a surtout travaillé avec des personnes qui connaissaient soit le magazine soit mon travail, mais à présent on nous approche pour collaborer sur une pub dans Periodico. » Pour une marque ou une institution, la commande d’une publicité devient donc une manière d’emprunter la voix du magazine et de se présenter comme de vrais partenaires d’une entreprise culturelle.

For a brand or institution, commissioning an ad becomes a way to present themselves as true partners to a cultural enterprise.

Pour une marque ou une institution, la commande d’une publicité devient une manière de se présenter comme de vrais partenaires d’une entreprise culturelle.

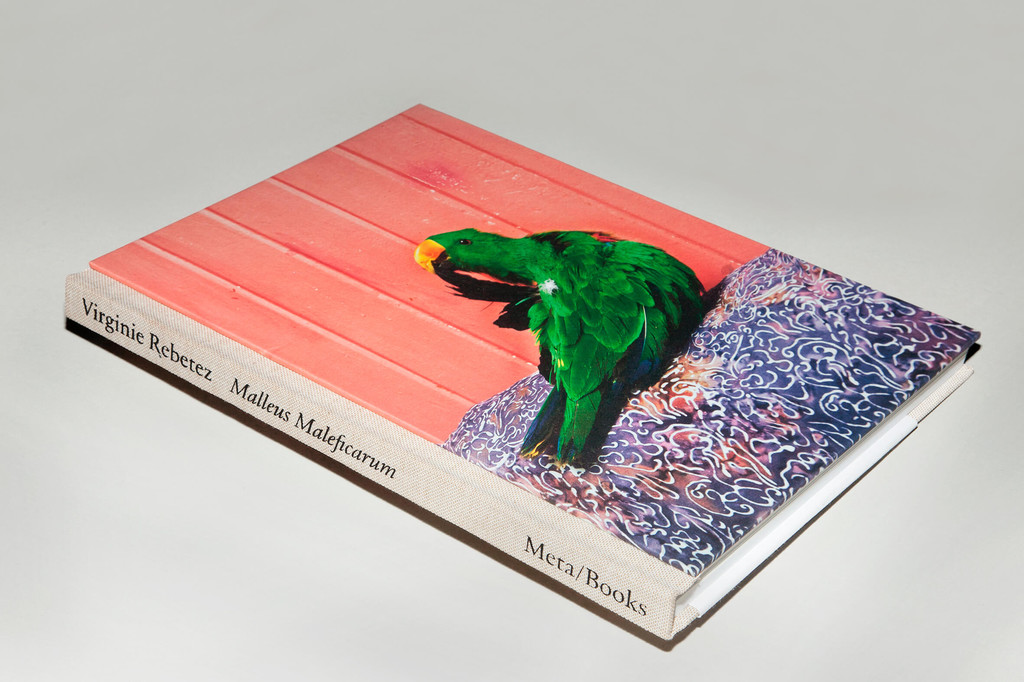

Another photographer, Virginie Rebetez presents work she developed as part of Fribourg’s photographic investigation. The commission is a biyearly call for projects, open to all professional photographers, that aims to support the field by selecting one project whose theme or topic concerns the canton. It is an unusual format because once the proposal is accepted, the photographer has almost complete freedom to develop their work independently over two years. Rebetez wanted to retell the story of Claude Bergier, who was accused of witchcraft and burnt in 1628, by collaborating with mediums and healers. She worked closely with them over a series of meetings and asked them to contact Bergier. To convey the story, the book and exhibition layer two voices: her work as a photographer and texts transcribing her sessions with the mediums. In the publication, it is as if she brings all the actors around the same table. The book is, therefore, a vessel gathering voices in a subtle alchemy. The object came to life through a careful joint effort with the publisher, Meta/Books, and the book designer, Chi-Long Trieu. The triad (photographer, publisher and designer) becomes tetrad when the final collaborator — the public — sits at the table. The active part played by the audience is indeed necessary to recompose the puzzle and interpret Bergier’s story.

Egalement photographe, Virginie Rebetez présente un travail qu’elle a développé dans le cadre de l’Enquête photographique fribourgeoise. La commande est un appel à projet bisannuel ouvert aux photographes professionnel·le·s qui vise à soutenir le domaine à travers la sélection d’un projet dont le thème concerne le canton. C’est un format inhabituel dans le sens où une fois leur projet accepté, les photographes travaillent en liberté quasiment totale sur une période de deux ans. Rebetez a choisi de raconter l’histoire de Claude Bergier, qui fut accusé de sorcellerie et brûlé vif en 1628, à travers une collaboration avec des médiums. Elle a travaillé de manière très proche avec ces derniers sur plusieurs rendez-vous et leur a demandé d’entrer en contact avec Bergier. Pour transmettre l’histoire de ce dernier, le livre et l’exposition qui forment le résultat de l’enquête mélangent deux voix : la photographie de Rebetez et les transcriptions des séances de cette dernière avec les médiums. Dans la publication, c’est comme si elle faisait se rejoindre les différents acteurs de l’histoire autour d’une même table. Le livre est donc comme un vaisseau qui rassemble toutes ces voix dans une alchimie subtile. L’objet est le résultat d’une collaboration méticuleuse avec la maison d’édition Meta/Books et le designer du livre, Chi-Long Trieu. La triade (photographe, éditeur et designer) devient tétrade quand le collaborateur final – le public – s’assied à cette table. Le rôle actif joué par l’audience est en effet nécessaire pour recomposer le puzzle et réinterpréter l’histoire de Bergier.

The work of graphic designers Simon Palmieri and Régis Tosetti sheds light on a different type of collaboration with the client. The close relationship they have developed with fashion designer Christopher Ræburn over ten years allowed to turn a simple commission into an extraordinary partnership. The duo began by designing the brand’s logo before developing its full range of communications materials. Once trust was established, the collaboration bloomed and materialised between the needs and desires of both sides. Palmieri and Tosetti are now going beyond the usual graphic design brief by designing prints for the clothes, set designs for shows and sounds for campaigns. Thanks to this long-term relationship, the duo thus works in complete symbiosis with the client, who benefits from the collaboration as much as the designers do.

Le travail des designers graphiques Simon Palmieri et Régis Tosetti permet de mieux saisir un autre type de collaboration avec le client. La relation très proche qu’ils ont développée en 10 ans avec le designer de mode Christopher Ræburn sur une période de dix ans leur a permis de transformer un simple mandat en un partenariat extraordinaire. Le duo a commencé par dessiner le logo de la marque avant de développer un éventail complet de matériel de communication. Dès que la confiance fut établie, la collaboration s’est épanouie de manière à se matérialiser entre les besoins et les désirs de chacun des côtés. Le rôle de Palmieri et Tosetti s’étend aujourd’hui bien au-delà du mandat habituel du design graphique : ils conçoivent des imprimés pour les habits, des scénographies pour les défilés et des univers sonores pour les campagnes. Grâce à cette relation de longue durée, le duo travaille en symbiose complète avec le client, qui bénéficie de la collaboration tout autant que les designers.

Once trust was established, the collaboration bloomed.

A partir du moment où la confiance fut établie, la collaboration s’est épanouie.

Set designer Daniel Zamarbide (working as BUREAU) goes one step further in his professional relationships. He rejects the notion of the client, avoiding the word “since the client-service relation implies a commercial rapport forcing one to comply with the other’s expectations as long as there is a monetary exchange.” Instead, he favours a collaborative dynamic within his work. Reflecting on his influences, Zamarbide cites the work of sociologist Richard Sennett, notably The Craftsman (2008) and Together (2012) as theoretical foundations. In the former, Sennett argues that we all have an innate desire to make things well; in the latter, he proposes that we need to do it in co-operation. These ideas resonate with Zamarbide, who has always needed to confront his own creative agenda and has therefore embraced working with others.

Le scénographe Daniel Zamarbide (qui travaille sous le nom de BUREAU) va encore plus loin dans ses relations professionnelles. Il rejette la notion de client, préférant éviter le mot « puisque la relation client-service implique un rapport commercial qui force l’un à se plier aux attentes de l’autre, tant qu’il y a un échange monétaire. » Au lieu de ce rapport, il préfère une dynamique collaborative dans son travail. Réfléchissant à ses influences, Zamarbide cite, comme base théorique, le travail du sociologue Richard Sennett, notamment The Craftsman (2008) et Together (2012)Ces ouvrages ont été traduits en français sous les titres “Ce que sait la main”, 2010, et “Ensemble”, 2013.. Dans le premier, Sennett avance que nous avons un désir inné de faire un travail artisanal de qualité ; dans le deuxième, il argumente que nous avons besoin de le faire en coopération. Ces idées trouvent un écho en Zamarbide, qui a toujours cherché la collaboration avec d’autres, dont il confronte le travail à son propre agenda créatif.

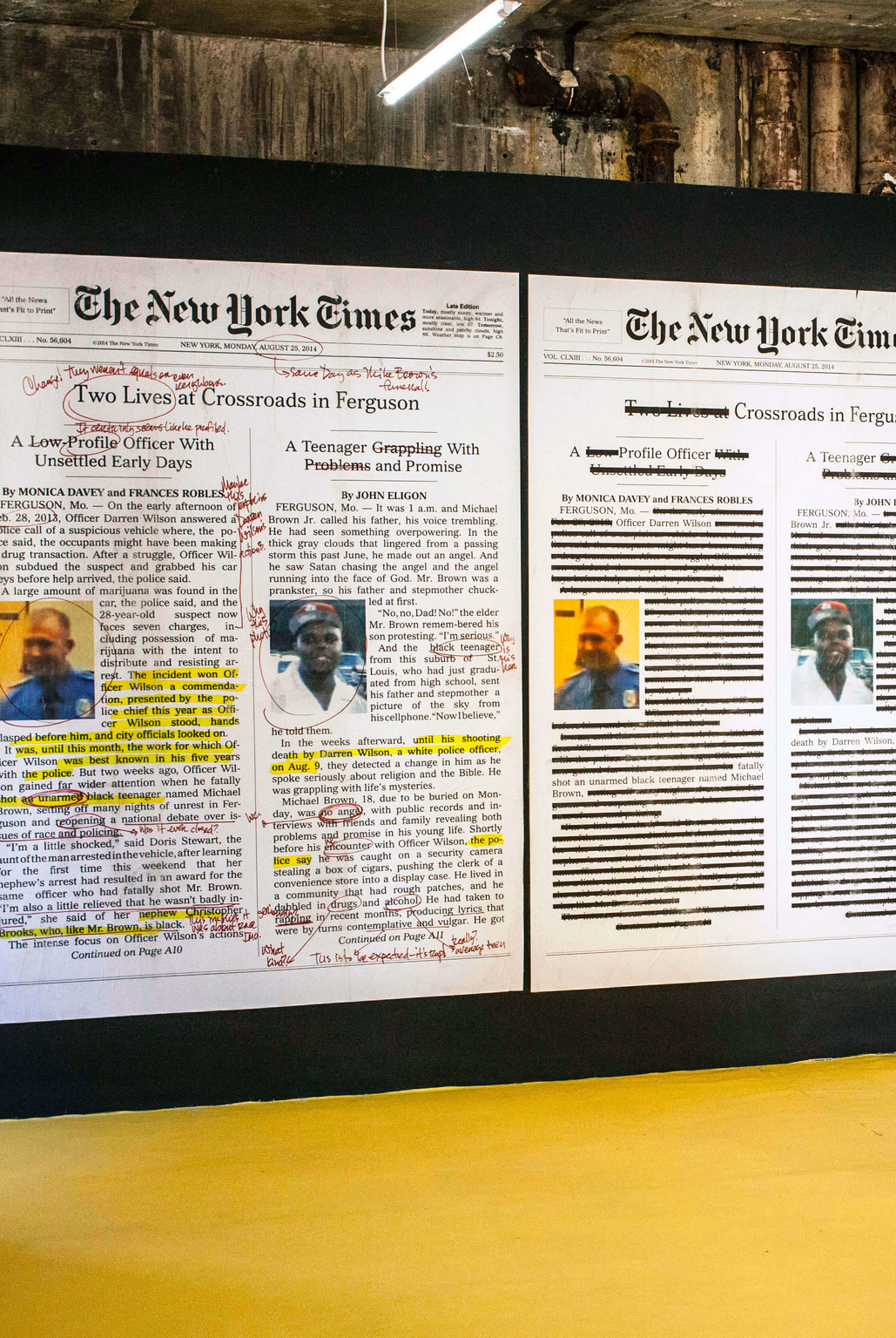

Nominated in the mediation category, the platform depatriarchise design (currently co-run by Maya Ober and Anja Neidhardt) also fundamentally relies on working with others. They use an intersectional approach to feminism and must, therefore, collaborate with a wide range of people to build on common political ground. But rather than seeing itself as a facilitator of empowerment, the platform enlists every reader as a potential collaborator in the resistance against patriarchy. For depatriarchise design, “collaboration is based on common ground and generosity; it gives hope.” The collective resistance aims to be transparent and non-hierarchical, and the organisers hence want to take this opportunity to acknowledge the collaborators on their platform.

Nominée dans la catégorie médiation, la platforme depatriarchise design (actuellement cogérée par Maya Ober et Anja Neidhardt) dépend fondamentalement du travail avec l’autre. Le projet utilise une approche intersectionnelle du féminisme et collabore ainsi avec un large éventail d’intéressé·e·s afin de construire un discours à partir d’une conception politique commune. Mais plutôt que de se voir comme des facilitatrices de l’émancipation, les cogérantes mettent en avant la plateforme comme le moyen de mobiliser chaque lectrice/lecteur comme une collaboratrice potentielle/un collaborateur potentiel dans la résistance contre le patriarcat. Pour depatriarchise design, « la collaboration se base sur une base commune et sur la générosité ; elle offre de l’espoir. » La résistance collective vise à être transparente et non-hiérarchique, et les organisatrices saisissent donc cette opportunité pour saluer les collaboratrices de la plateforme.

Rather than seeing itself as a facilitator of empowerment, the platform enlists every reader as a potential collaborator in the resistance against patriarchy.

Plutôt que de se voir comme des facilitatrices de l’émancipation, les cogérantes mettent en avant la plateforme comme le moyen de mobiliser chaque lectrice comme une collaboratrice potentielle dans la résistance contre le patriarcat.

Photographers Yann Gross and Arguiñe Escandon rely on a delicate collaboration with the other while avoiding othering. Their project Aya was developed over two years and retraces the steps of Charles Kroehle, a photographer who took the first pictures in the Peruvian Amazon between 1888 and 1892. Treading carefully to avoid cultural appropriation — Kroehle was an archetypal colonial adventurer, and his images relied heavily on exoticism — Escandon and Gross set on the self-admitted impossible endeavour of striving to erase the distance of observation, and thus avoiding the use of photography as a colonial instrument of representation, by becoming subjects themselves. Their first step was to defocus their gaze by spending time in the jungle, feeding on plants and observing the indigenous communities’ relationship with their environment. They then translated their observations in images. Escandon has an emotional approach to image-making, while Gross is more methodical. These complementing aspects of their collaboration helped them to interact with each subject differently and to build a more complex representation of their experiences.

Les photographes Yann Gross et Arguiñe Escandon s’appuient sur une collaboration délicate avec l’« autre », tout en évitant l’altérité. Leur projet Aya a été développé sur une période de deux ans et retrace le parcours de Charles Kroehle, un photographe qui prit les premières images de l’Amazonie péruvienne, entre 1888 et 1892. Travaillant prudemment afin d’éviter l’appropriation culturelle – Kroehle était un aventurier colonial archétypal, et ses images font preuve d’un exotisme exacerbé – Escandon et Gross s’efforcent d’effacer la distance créée par l’observation, une mission qu’ils reconnaissent d’avance comme impossible. Pour éviter d’utiliser la photographie comme un instrument colonial de représentation, ils deviennent eux-mêmes sujets de leur projet. La première étape fut de « dé-focaliser » leur regard en passant du temps dans la jungle, se nourrissant de plantes et observant la relation que les communautés indigènes ont avec leur environnement. Les photographes ont ensuite traduit leurs observations en images. Escandon a une approche émotionnelle, tandis que Gross est méthodique ; ces aspects complémentaires de leur collaboration les ont aidés à interagir différemment avec chaque sujet et de construire une représentation plus complexe de leurs expériences.

To avoid using photography as a colonial instrument of representation, they become subjects themselves.

Pour éviter d’utiliser la photographie comme un instrument colonial de représentation, ils deviennent eux-mêmes sujets de leur projet.

Collaboration abounds. Whether through teamwork, partnership or alliance, design relies heavily on the other to deliver projects that are more accomplished or more complex than if they had been attempted independently. The actual process is separate in each case as designers have distinctive working methods: collaboration is thus always different. Because it fuses practitioners’ interests with their partners’, the process can leave a lasting trace. Furthermore, perhaps in line with our constant presence on social media, notions of collaboration with an audience have become more relevant than ever. All these aspects are parts of the reason why we strive to team up with others.

Les instances de collaboration abondent. Que ce soit à travers le travail d’équipe, le partenariat ou l’alliance, le design dépend considérablement sur l’autre pour produire des travaux qui soient plus accomplis ou plus complexes qu’ils n’auraient pu l’être s’ils avaient été réalisés par un seul créateur. Le processus même varie au cas par cas, puisque les designers ont des méthodes de travail distinctes. La collaboration est donc différente à chaque occasion. Puisque le processus fusionne les intérêts des designers avec ceux de leurs partenaires, il laisse souvent une trace durable. Par ailleurs, peut-être de concert avec notre présence constante sur les médias sociaux, la notion de collaboration avec une audience est plus pertinente que jamais. Tous ces aspects fondent notre aspiration à faire équipe avec d’autres.

Only by seeking the difference in collaboration will we be able to make our best work, and achieve a better world.

C’est seulement en cherchant la différence dans la collaboration que nous pourrons faire notre travail de manière optimale – et atteindre un monde meilleur.

Professional cooperation has been present forever, but some aspects are unique to our times. It is clear that the profusion of digital tools facilitates nomad, fluid partnerships that form and disappear as they are needed. The mental image of the network should thus be pictured as a protean, flowing, temporary relationship. It links subcultures, beliefs and appreciation — rather than, as we might traditionally imagine it, closed old boys’ networks, contracts or predetermined exchange. At a recent conference in Bern, design writer and curator Emily King shared an insight she gained while working on a piece.Emily King, “Curating and Writing Beyond Academia”, conference at University of Bern, Bern, 4 April 2019; Emily King, “Leila McAlister”, in: “The Gentlewoman” 6, 2012. It seems like fromagers cannot rely purely on their own cheese cultures in the long term: they have to share them with other dairies to avoid weakening bacteria. Expanding on this cheesy metaphor is somehow quite fitting for the design world. If we want to build a sustainable and sustaining design practice, we must abide by the real power of sharing, which is about the “and” rather than the “either/or”. This seems to be especially relevant this year, as we notice a number of projects dealing with social engagement such as real-world issues, gender, identity, race and power dynamics. It confirms the importance of engaging with the other. Only by seeking the difference in collaboration will we be able to make our best work, and achieve a better world.

La collaboration professionnelle a toujours été présente, mais certains aspects sont propres à notre époque. Il est clair que la profusion d’outils digitaux facilite des partenariats fluides et nomades qui se forment et disparaissent au fur et à mesure des besoins. L’image mentale du réseau devrait donc refléter une relation protéiforme, fluctuante et temporaire. Elle relie les subcultures, les croyances et l’appréciation pour autrui – plutôt que, comme on pourrait traditionnellement l’imaginer, des clubs fermés de vieux copains, des contrats ou des échanges prédéterminés. Récemment, lors d’une conférence à Berne, Emily King a fait part d’une information fascinante qu’elle a découverte lorsqu’elle travaillait sur un article.Emily King, “Curating and Writing Beyond Academia”, conférence à l’université de Berne, Berne, 4 Avril 2019; Emily King, “Leila McAlister”, in: “The Gentlewoman” 6, 2012. Il semblerait que les fromagers ne peuvent pas garder jalousement les cultures qui leur sont nécessaires à la fabrication du fromage. Sur le long terme, les bactéries s’affaiblissent, et il est donc nécessaire de collaborer avec d’autres fromageries en mélangeant ces ferments. Cette métaphore un peu cheesy est d’une certaine manière applicable au monde du design. Si nous voulons construire une pratique durable qui nous nourrisse, nous devons soutenir le potentiel du partage, qui concerne le « et » plutôt que le « ou ». Ce sujet semble être particulièrement pertinent cette année, où nous constatons un grand nombre de projets qui démontrent un engagement social à travers des thèmes et des propositions pour des problèmes réels : le genre, l’identité, la race et les dynamiques du pouvoir. Cela confirme l’importance de s’impliquer avec l’autre : c’est seulement en cherchant la différence dans la collaboration que nous pourrons faire notre travail de manière optimale – et atteindre un monde meilleur.

Jonas Berthod is a graphic designer, researcher and writer based in London. He is a PhD candidate in design history, a lecturer at ECAL and a visiting lecturer at the Royal College of Art. Existing between theory and practice, his work spans a wide range of topics connected to design.

Jonas Berthod est un designer graphique, chercheur et écrivain basé à Londres. Doctorant en histoire du design graphique, il enseigne également à l'ECAL et au Royal College of Art. Son travail, entre pratique et théorie, couvre une série de sujets liés au design.