ISKANDER GUETTA in conversation with COMMON-INTEREST (Corinne Gisel & Nina Paim)

Interview Iskander Guetta

Making Politics out

of Design and

Design out of Politics

COMMON-INTEREST: Could you briefly introduce your project Abri+?

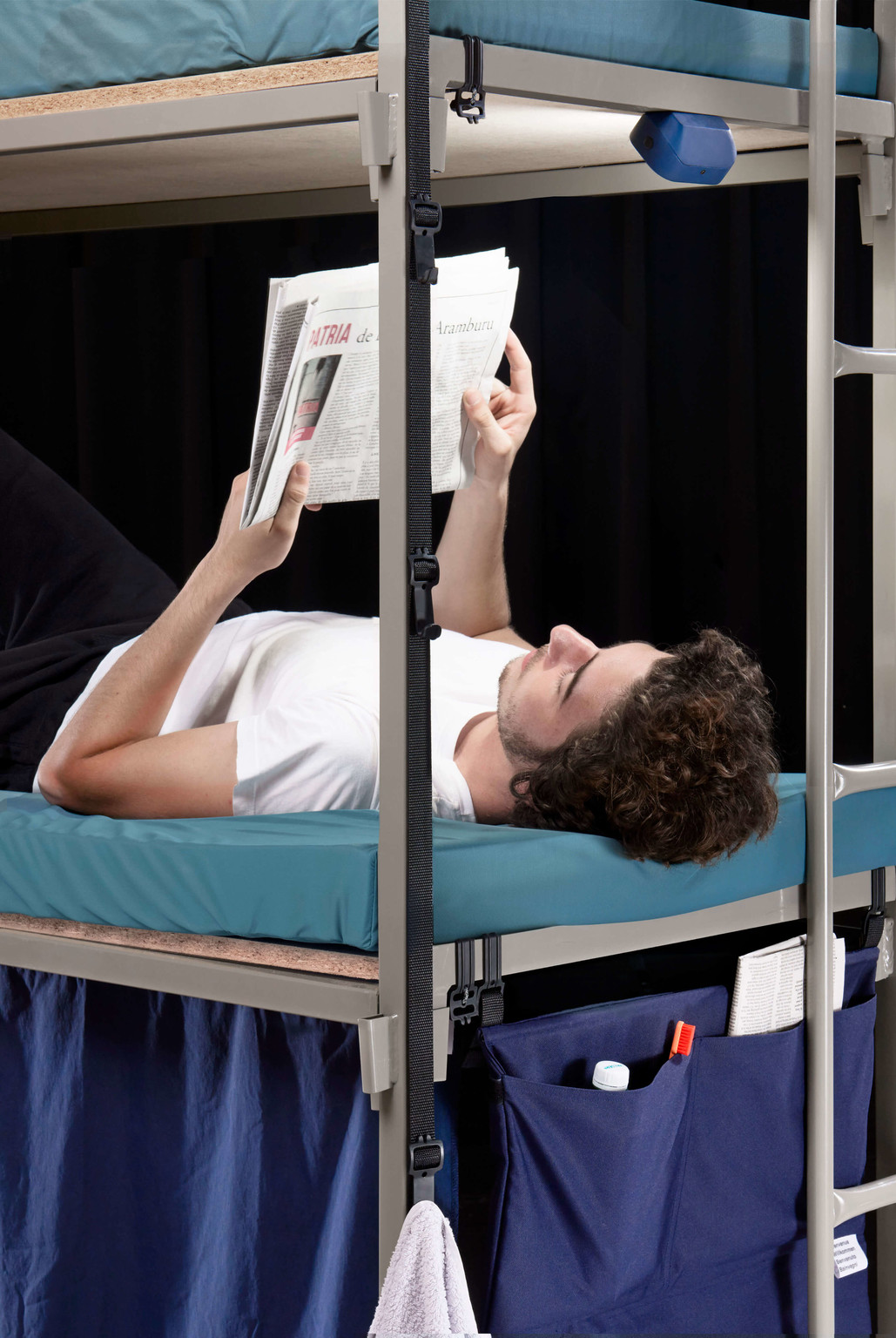

ISKANDER GUETTA: Abri+ is a set of objects for Swiss dormitory bunkers. During the Cold War, Switzerland started building underground nuclear fallout shelters for its population. Since then, by law, municipalities and real estate owners must ensure that in case of a civil catastrophe, each inhabitant has a secured spot in a bunker. During peacetime, these bunkers can be requisitioned for emergency situations and are often used to temporarily host people who are without homes — people who were displaced due to natural disasters, homeless people who are looking for a warm place to sleep during winter, and in recent years also people who were officially seeking asylum in Switzerland. Abri+ consist of a curtain, a set of hooks, a portable lamp, and hanging pockets — all can be attached to the standardized bunk beds in these underground shelters. The set gives the residents a little more intimacy and privacy, using the only space they have for themselves: their spot in one of those bunk beds.

Swiss fallout shelters can be requisitioned for emergency situations and are often used to temporarily host people who are without homes.

C-I: How did the project come about?

ISK: The first time I heard about migrants and asylum seekers being housed in bunkers was in a newspaper article I read during my second year at ECAL (Lausanne University of Art and Design) in 2015. There was a sensationalist undertone, stating that there were “so many” migrants and asylum seekers that the government had to open up bunkers as temporary housing solutions. At first, the media did not mention the extremely precarious living condition in these bunkers. It was more about justifying the inability to host them in more appropriate housing. Only after a couple of demonstrations in the Swiss cities of Lausanne and Geneva in 2015, some people realized the gravity of what was happening right under their feet. In 2017, in my third and graduation year at ECAL, the teachers asked us to either look for problems we could solve or think of a topic that would interest us. This is when I remembered the bunkers and started researching the situation in more detail.

The first step was to understand from the beginning how migrants and asylum seekers are hosted in Switzerland, and how it happened that some of them spent so much time in those bunkers. I got in touch with EVAM (the Etablissement Vaudois d’Accueil des Migrants), the institution that manages the hosting of migrants in the Swiss canton of Vaud. Catherine Martin, manager of housing units at EVAM, explained that usually, migrants and asylum seekers are housed in flats, which means they live in a real house, where they have household amenities, domestic furniture, and enough space for privacy. However, between circa 2014 and 2016, there was a shortage of available spots for migrants and asylum seekers in conventional buildings. The Federal Office for Civil Protection FOCP, the governmental unit that manages the use of the fallout shelters, granted EVAM the use of bunkers. The interior and furnishing of those underground bunkers is only adapted to short-term living during extreme emergency situations.

By the time I had started my research, the practice of hosting migrants in bunkers had dissipated again due to a drop in asylum applications. But the laws and policies around these “emergency” solutions are very complicated, and it might well happen again. When I asked Catherine Martin whether they had any solutions to improve the living situation in these bunkers, she told me that there simply isn’t one, because the occupation is always considered “temporary.” EVAM tried to make the stays in those bunkers as short as possible, but sometimes people ended up being there for over six months, sometimes even for more than one year. It’s a paradox of the system. Everybody knows the living conditions in these bunkers are rough, but no serious conversations are held about potential solutions because nobody thinks it’s worth investing in finding a solution for a “temporary” case.

It’s a paradox of the system. Everybody knows the living conditions in these bunkers are rough, but because they are temporary, no serious conversation about potential solutions is taking place.

C-I: How did you go about turning that into a design project?

ISK: The first question was how I, as a product designer, could approach this problem through materials and objects. Earlier in the process, I had met with an expert for the furnishing, regulation, and maintenance of Swiss bunkers. Every single piece of furniture, from the shower curtain to the cushion, is standardized and has to fit within the federal norms for these fallout bunkers. As a designer, this was an interesting starting point, because it meant that I could produce a standard object that would again fit within these Swiss norms, which meant it could be used in any bunker in the country. To better understand the problems of living in those bunkers, I watched a few films, for instance the 2016 documentary “Bunkers,” by Anne-Claire Adet. I also met with another person from EVAM, who was responsible for the objects that are provided to the migrants and asylum seekers who were housed in the bunkers. And that’s minimal: basically just bed sheets, cutlery, and a cushion. Through discussions with this person, it became clear that the most crucial issue was the lack of intimate space. Then the question was, whether I should focus on the dormitory, the bathroom, the common spaces, or whether I should intervene in all spaces? I decided to focus on the dormitory, and from that to work on the standard bed and the standard items given to residents.

It became clear that the most crucial issue was the lack of intimate space.

C-I: How did you experience the bunkers?

ISK: The first bunker I visited was just outside the centre of Lausanne. This one is used to host homeless people during the colder seasons, from October until March. They provide a meal and breakfast, as well as clean bed sheets and a cushion for each of the approximately sixty residents every night. All residents must leave the bunker again at 8am. The facility manager of this bunker met me there at 9am, after everyone had left. As we entered, we first went down a 50 meter concrete tunnel. After passing through two transfer airlocks, separated by concrete doors thicker than a tree trunk, we arrived in the common space. The space felt really official, straight, and rigid. All of the infrastructure was standardized. Everything had the same color, the same tables, chairs, walls. It made me think of a prison. There were two dormitories — one for men, the other for women, and one room for the watchman. Sometimes they made an exception and let a couple sleep together, separated from the other residents with a curtain made from a sheet. Lit by white neon lamps, everything seemed faded and cold. The air was stale, and in rather short supply, with some lingering scents of what reminded me of dirty laundry. The only relation with the passing of time came from a clock that hung on a wall in the common room. Being 15 feet underground, one feels cut off from the real world. All of the bunkers I saw looked similar. The facility manager I met was skeptical about finding furniture or object solutions when it comes to the housing of homeless people. They simply don’t know if people will come back or not, so there’s no follow-up on the residents. The second bunker I visited was in the upper part of the city of Lausanne, underneath a college. This one was managed by the EVAM and had previously been used to host migrants and asylum seekers. Residents spent the day outside, but came back down every night, to their designated bed. This also meant that a design solution would be easier to apply and could have a real impact. I was told that the residents were spontaneously finding solutions to create a more private space for themselves, using bed sheets as curtains, or the light of their phones as lamps — simple solutions with simple means. I tried to do the same in my design process, but making solutions that were more durable and more practical.

C-I: What did your design process look like after that?

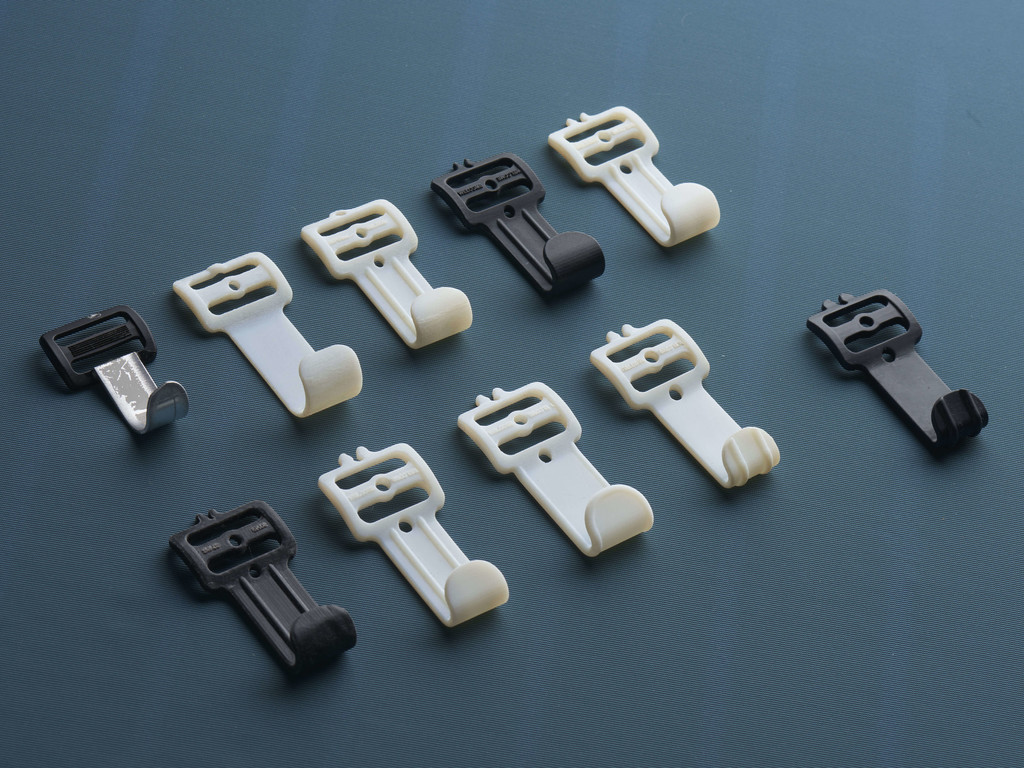

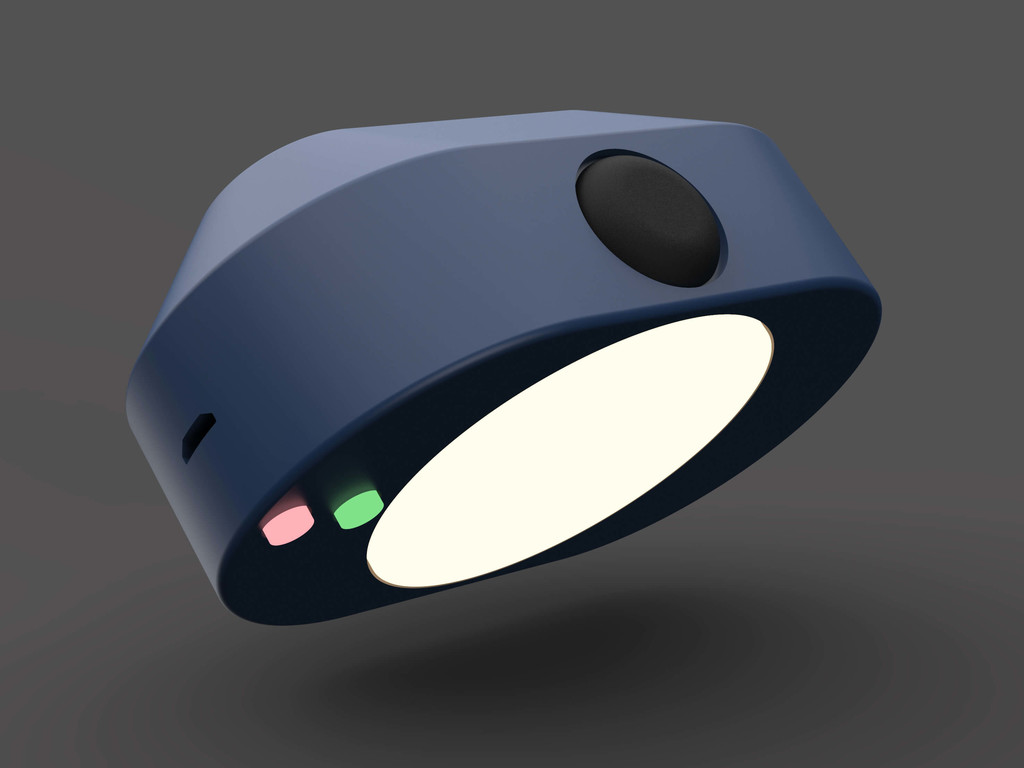

ISK: I had started my research in December 2017 and concluded that phase at the end of January 2018. From then on until the end of June 2018 I focused on the development and materialization of the objects. I was able to borrow one of those bunk beds from the Federal Office for Civil Protection, and that was the starting point for the practical part of the design process. By having an actual shelter bunk bed sitting in my classroom, I could get a sense of what it felt like to spend time in it. I did a lot of sketching at the beginning, but very quickly started to simply try things directly on the actual bed. The first piece I designed was the hook. As I was trying to find a way to hang the curtain and the pocket, I realised that having just one piece to install all the elements would be cheaper and more efficient. So the same element can be used to stretch the curtain, to hang the pocket, and also simply as a hook. From that I was able to develop the whole set. I thought the items should be simple, coherent, and silent. That is to say, they should not look like a big mix or be visually noisy or flashy, because those spaces are already so hard to live in, and I didn’t want to impose myself as a designer. As the main color, I picked a dark hue of blue, referring to the night’s sky. A small tag that says “Welcome” in the four official languages of Switzerland — French, German, Italian, and Romansh —, as is often the case in communication materials of Federal Institutions, gave the set that kind of Swiss identity.

By having an actual shelter bunk bed in my classroom, i could get a sense of what it felt like to spend time in it.

C-I: What were some of your references while developing the objects?

ISK: I explored what kind of objects public dormitories, even for children, and youth hostels around the world provide. From that, I looked at standardized institutional spaces, such as prisons, where people have to spend a lot of time and find spontaneous solutions by themselves. I think prison cells was perhaps the most important reference for me, as it talks to the almost primary need that motivates people to make objects and design contraptions. A lot of prisoners make curtains, for example. They are trying to find solutions in their cells with the few things they have at their disposal. It’s a very tough space to find your own intimacy and comfort. And the institution doesn’t necessarily want you to be comfortable, since you are being punished. So you have to find your own space and comfort without the authorization or help from your host.

I also examined objects made for the International Space Station. The residents of that station were all allocated what they called a “sleep station,” which provided them with a place of intimacy while sleeping or resting. The physical conditions in a space station are so extreme that one can easily identify how they appropriate and personalize the space and how a privacy pod, a comfortable and familiar place, is absolutely elementary, especially in such a context. Further design references came from how cabins in submarines or trains and night trains are designed. For instance, Indian night train cabins reveal a very basic infrastructure that can be offered in the context of a temporary shared dormitory. I also looked at Swiss trains, buses, train stations, and other Swiss common spaces, to understand how Switzerland creates identity in a space where so many people pass through and spend time. Furthermore, I came across some interesting ideas about modularity in housing systems. But it always circled back to questions such as ‘what is needed to create an intimate and private space?’, or ‘how one can feel okay around a lot of people?’

C-I: Did you also look into how other designers or projects engaged with a similar political situation, i.e. the hosting of people seeking refuge?

ISK: It’s very complex, because the situation is different in every country. When looking for design references, one can quickly find lots of projects online, such as the “IKEA refugee home” or the “Rehome” project by Lahti university students. Many of these projects are actually quite famous — at least in Western design media. However, in general, most of these projects are “global solutions,” which in my opinion is a very treacherous thing. Most design projects I found about housing migrants across Europe took this universal-solutionism approach that was not really linked to any kind of public institution or governmental housing system. It was mostly solutions created by designers to house migrants in the streets, in the park, or other precarious spaces. They were not really legal or realistic solutions that were in discussion with the state system or the institutional housing system. Another point is that most of the those projects are framed as “refugee projects,”which automatically creates a distinction between those who were displaced from their homes now seeking refuge in another country and the rest of the population.

We can clearly see that in the Zaatari camp in Jordania. At first, it was spontaneously constructed by Syrian refugees looking for a place to sleep. When the Jordanian state, with the help of the UNHCR (UN refugee agency), decided to make it official, they came up with this “refugee city” solution, conceived by Western architects. By 2013, the camp had become the fifth biggest city in Jordania, counting roughly 200,000 residents. Instead of creating normal buildings or a setup that would have allowed for these residents to be integrated into Jordanian city life, the concept of the “refugee city” created a very clear distinction, singling out those people who, because of their “refugeeness,” have to live in this temporary and precarious city. In my opinion, designers should actually face up to the responsibility of making projects out of a specific local context. However, it seems to be very hard for designers not to try to save the whole world, and not to think of universally applicable solutions. Maybe this is something that is being so imprinted on us by design media and design education. Maybe designers should stop looking for global solutions and try to first find solutions from their own immediate context.

C-I: What were some of the reactions from teachers and classmates to your project?

ISK: My classmates enjoyed the fact that I was able to start working from a very real framework: The bed. I had to make something out of the space, proportions, and dimensions given by the bed. My teachers also appreciated that side of the project, working with a real context, but they were skeptical of the political discourse I was getting myself into, as it was a very sensitive subject. They were afraid that I would hide behind the subject. Because they thought the political topic would take up too much space, that in the end it would be more about politics than the actual final object. They actually tried to convince me to do something else. At first, I listened to them. I found another idea, which was to make an outdoor espresso machine to be used by hikers in the mountains. That project would have been much more about finding a technically savvy, and sexy solution. It might be interesting as a designer to make those kind of objects, but looking at it from a social or global perspective, there’s not really anything behind those fanciful things. They don’t add anything critical to the times we are living in and the problems we are facing. I would have been very disappointed if I had to make an object like that. So I eventually chose to go against the advice of my teachers and continued with the topic of underground shelter living.

Designers should actually face up to the responsibility of making projects out of a specific local context.

C-I: How did you navigate that fear of you disappearing in the political shadow of the project that your teachers had voiced?

ISK: During the whole practical development of the project, from February till June, I didn’t mention anything about the political context of the bunkers, neither during presentations nor in meetings with teachers. I knew that in order to have a good and effective result I will have to concentrate 100 % on solving a material problem and not on trying to translate political opinion into objects. This way, the political aspect would be more the essence of the project and not its sole purpose. While I did start from a specific local situation, during the actual design of the objects, I consciously took a step back from the political context. It became about having that bed and dealing with very pure questions of materiality. It was as if I was making any kind of objects for anyone. I wanted the objects to be designed for really anyone who would sleep in such bunk beds. But all the while I was still further engaging with the political issue that started my project. Because, at the end, the real need and political situation was the generator for the energy I put into this project.

C-I: Framing these objects as “for everyone” also seems to resonate in the photographs you made to represent your project. How did you art direct those images?

ISK: At ECAL it’s very common to make a “sexy shooting” at the end of your diploma. The challenge was to make a documentation of such a politically motivated project that would fit with my thoughts and meet the school’s expectations. Working with a good friend of mine, Vincent Levrat, who is a brilliant photographer of objects, I decided to stage the objects on the original bunk bed, but within a rather neutral photographic surrounding. The models and props we used also don’t allude to the political situation that motivated the project. So if you don’t know the original context of the project, you would think it’s just objects made for a bunk bed, you don’t know for whom. That kind of neutrality was very important to me. I wanted to present objects as if they were made for everyone. Had I designed or framed the objects with too much of a visual reference to the original political context, I would have further stigmatized the people affected by it as “migrants,” as something “other,” while they should be considered as simply part of “everyone.” Already calling them “migrants,” or “asylum seekers” dehumanizes them, and diminishes their identity to the legal status they are given when all they want is to find a better life. That’s as simple as it is. They should have the same rights and the same consideration as everyone who lives in Switzerland. And they deserve the same objects of comfort that every human being spending time in these underground shelters should be given.

C-I: How do you plan on continuing the project?

ISK: I think the best production partner would be the Swiss Government, because I would not want the set to be commercialized. I would like to get in touch with someone from the Swiss Confederation, and try to find a solution with them to make it real. Maybe it could be only the curtain, or a few pieces out of the set, but it would be great if the project could fulfil the purpose it was designed for. It should become what the name of the project expresses — “Abri” being the French word for shelter, the “+” alluding to an addition: not only an extension to the usual items that may be given to anyone spending more than one night in one of those underground bunkers, but also an expression that only giving someone a roof over their head is not enough. The “+” is an open indication, alluding to the “more” that we should do for newcomers. We have to give people more than just shelter, more than just a place in a Swiss bunker, but actually a place in Swiss society. And this starts by facing every individual’s basic need for intimacy and comfort, thereby giving them what everyone deserves.

C-I: What is next for you apart from Abri+?

ISK: I’m still very young, just coming out of my studies, without much experience, and I’m actually rather afraid of how the professional world might transform someone who cares about political issues into a worker for the industry. I see lots of young designers going on to do internships at design and furniture companies, creating things for which there seems to be a lack of reasons why these objects are even made and brought into the world in the first place. Reasons beyond the form itself, beyond getting sold, beyond merely proving that you, the designer, can make appealing forms and sellable designs. There seems to be a widespread lack of responsibility in product design. The Western system of capitalist thought is so pervasive that we all forget why we are doing things and for whom. I, however, believe that as a designer you are responsible for how your design is produced, whom are you making it for, or how it will be sold. Is it really sensible to still make furniture and objects just for the sake of adding to a high-brow culture or a profit-oriented market? For me, design has really lots to do with politics — always and everywhere. What I’m trying to solve in my own mind at this moment is how I will be able to make politics out of design, and how I will be able to make design out of politics.

What I’m trying to solve in my own mind at this moment is how i will be able to make politics out of design, and how i will be able to make design out of politics.

C-I: Would you then describe yourself as a design activist?

ISK: Just by being a designer you are already an activist. By doing nothing you are an activist for the dominant world system that we are living in, which is a terrible one. By not making any so-called political choices, you are actually choosing to support the system as it is. You might think you are simply producing objects for the industry, that that is some sort of a neutral thing to do, but in fact everything you create maintains and sustains the disparity and nonsense of our actual system. By creating objects in the hope that they will be featured in a design magazine or shown at Milan Design Week — which is happening right now as we are talking — you are creating the material distinction of our era. These objects are made for a very specific part of society. Those pretended “new designs” are in fact just new tools for further social distinction. Making those objects then becomes a political act, you are materializing the differences between social classes. It is a kind of unconscious counter-activism for the system that creates social stigmatization in the first place.

C-I: How do you navigate that yourself?

ISK: I’m still in the process of understanding how design impacts social class. At ECAL, I made a lot of fancy objects that were completely devoid of substance. The path after this particular school is quite clearly set out, with graduates doing internships and afterward finding a secure place in the professional world. Nevertheless, before I do go down that road, I am wondering: why work within and for a system that is both creating social inequality and has also been destroying our planet? I don’t know yet how to go about this. I just spent six months in Morocco — my mother’s home country — and realized how much we should look for other perspectives beyond the Western-centric one. North-african countries like Morocco, have not yet completely fallen under the tyranny of neoliberalism. Despite a lack of political structure and healthcare, they have a lot to teach us, from social relations to recycling and producing in a sustainable way. I want to spend much more time in North Africa and the African continent in general. Because I think the dominant European or North American systems have already shown how we are really going in the wrong direction. How we are getting more deeply into simply producing more services or more objects just for the sake of added comfort, or to increase the general speed of living. I want to see other systems and other perspectives.

This interview was created on the occasion of the exhibition Shelter Fallout—Swiss Design Awards at WantedDesign, which took place in Brooklyn, New York, in May 2019, and revolved around the project Abri+ by SDA nominee Iskander Guetta. The exhibition was accompanied by the panel discussion Up Against—Design Education and the Undercommons, a conversation between Mia Charlene White, Ramon Tejada, and Iskander Guetta, curated by SDA nominees common-interest (Corinne Gisel & Nina Paim). Both the exhibition as well as the panel discussion were presented by swissnex Boston, the Consulate General of Switzerland in New York, and the Federal Office of Culture – Switzerland.