Text by VERA SACCHETTI

Social Engagement

Not just another chair:

beyond

the industrial paradigm

An open-air room: only a shadow of what once was an industrial roof, derelict walls, a broken floor and plants growing in-between floor and wall joints. In this peaceful and impressive space, a series of diaphanous curtains and threads hang about, floating gently with the wind and revealing a few small pedestals where small objects are placed on display. One of the first spaces to be entered in the former panettone factory ALCOVA, which harboured some of the most impressive displays on show for this year’s Milan Design Week, this was the room where Swiss brand Qwstion (Christian Paul Kägi and Paolo Paoluzzo) showcased their waterproof and durable material Bananatex, a textile made of sustainably grown banana plant fibers.

Developed over the last four years, the new material is fully biodegradable. Qwestion points out “it has the potential to replace the technical plastic materials dominating the market for outdoor applications today.” Alongside the large sheets of textile and the threads hanging from a series of arches, the objects on the pedestals were several kinds of bags and backpacks developed by the brand, with simple lines and sturdy aspect. The Bananatex project, which behind the product opens up to reveal a different kind of mentality about material sustainability and social impact, was presented in 2018 as the brand celebrated its tenth anniversary. The banana plants — called Abacá — are organically cultivated within a natural ecosystem of sustainable mixed agriculture and forestry, in the highlands of the Philippines: The bags developed with the textile fulfill Qwstion’s goal to use only natural, organically grown fibers for the shell fabrics of their backpacks, paired with organic cotton in the lining.

“This way of working — concerned with sustainability, respectful of context and environment, and challenging traditional notions of authorship by engaging in open source experiments — is radically new for design.”

By using the Abacá plant as a main material source, Qwstion is also contributing to the reforestation in certain areas of the Philippines, which were previously eroded by palm plantations, and contributing to the economic prosperity of its farmers. Furthermore, the project is open source, and Qwstion want to encourage other brands to use Bananatex — obviously not only for backpacks. This way of working — concerned with sustainability, respectful of context and environment, and challenging traditional notions of authorship by engaging in open source experiments — is radically new for design, a discipline that has been traditionally more concerned with efficiency, large-scale production, and royalties derived from authorial obsession. Within the nominees of this year’s Swiss Design Awards, several designers choose to step out of the industrial paradigm and engage with the social sector in various degrees, immersing themselves in different contexts and upholding sustainability as an essential tenet. Qwstion is but one.

Economically, these steps for the reinvention of the design field are understandable when looking back the the events of the last decade. After the September 2008 crash, many companies focused on core activities and aimed towards unsaturated, underserved markets, the “bottom of the pyramid” and the low-end consumer, seeking to stay afloat. As Lehman Brothers collapsed and the subprime crisis unravelled, most of the world’s professions reassessed their priorities, and so did designers. In an effort to make amends for what the design critic Alice Rawsthorn has deemed the “great failure of twentieth-century design — neglecting the ‘other 90 per cent’, or the six billion people who are too poor to afford the basics”, they turned to the underprivileged. Simultaneously, design as a tool for innovation became a player on the world stage. At the World Economic Forum in Davos, designers became active participants and influencers in issues such as Future of Government, Humanitarian Assistance, Social Innovation, Values, Education and Climate Change. Design’s success in the corporate sector intrigued foundations and companies, who started applying it as a tool for innovation in the social sector. In schools, design students worked more than ever in projects for the social sector — partnering with professionals from other disciplines and seeking to make a more meaningful impact on the world than can be achieved through the design of a chair or a lamp.

“In her work, the designer [Julie Richoz] is part of a complex web of exchanges, learning as much (if not more) from the craftsperson than the other way around.”

Seen in this light, the work of Qwstion comes at the end of a continuum that has permeated the design field in the last decade. But within the nominees of this year’s Swiss Design Awards, other approaches about. Take for example the work of designer Julie Richoz, who in a series of residencies generated diverse outcomes that attest to an intense learning process with craftspeople from four different parts of the world, from France to Mexico via Taiwan. “All projects, yet initiated upon differents invitations, are sharing a specific context within which they were formulated,” Richoz points out. “A context of small production with local roots, a context of exploration and actualisation of traditional crafts, and of typologies that have accompanied humankind for centuries.” According to the designer, the objects — varying from expertly woven carpets to impeccably lacquered small objects — not only attest to the rich knowledge exchanges she had with the craftsmen, but also serve “to celebrate the most beautiful role objects carry in society: the means of communication between humans, through times and cultures.”

Richoz’s work highlights these craftspeople, bringing them to the front row and underlining their expertise and craft. In her work, the designer is part of a complex web of exchanges, learning as much (if not more) from the craftsperson than the other way around. In highlighting the knowledge and skills of others, Richoz is not alone. In a more poetic and oneiric way, the work of photographers Solène Gün and Yann Gross & Arguiñe Escandon does exactly the same, be it with a young Turkish community in the peripheries of Paris and Berlin, or with a multidimensional ethnographic exploration titled The Holes of the Tree. Conversely, the work of designer Iskander Guetta uses a very different type of social engagement as a driver.

“Projects such as these talk use ingrained ways of making and traditional design typologies to generate alternatives and possibilities, creating more complexity in times that are already convoluted.”

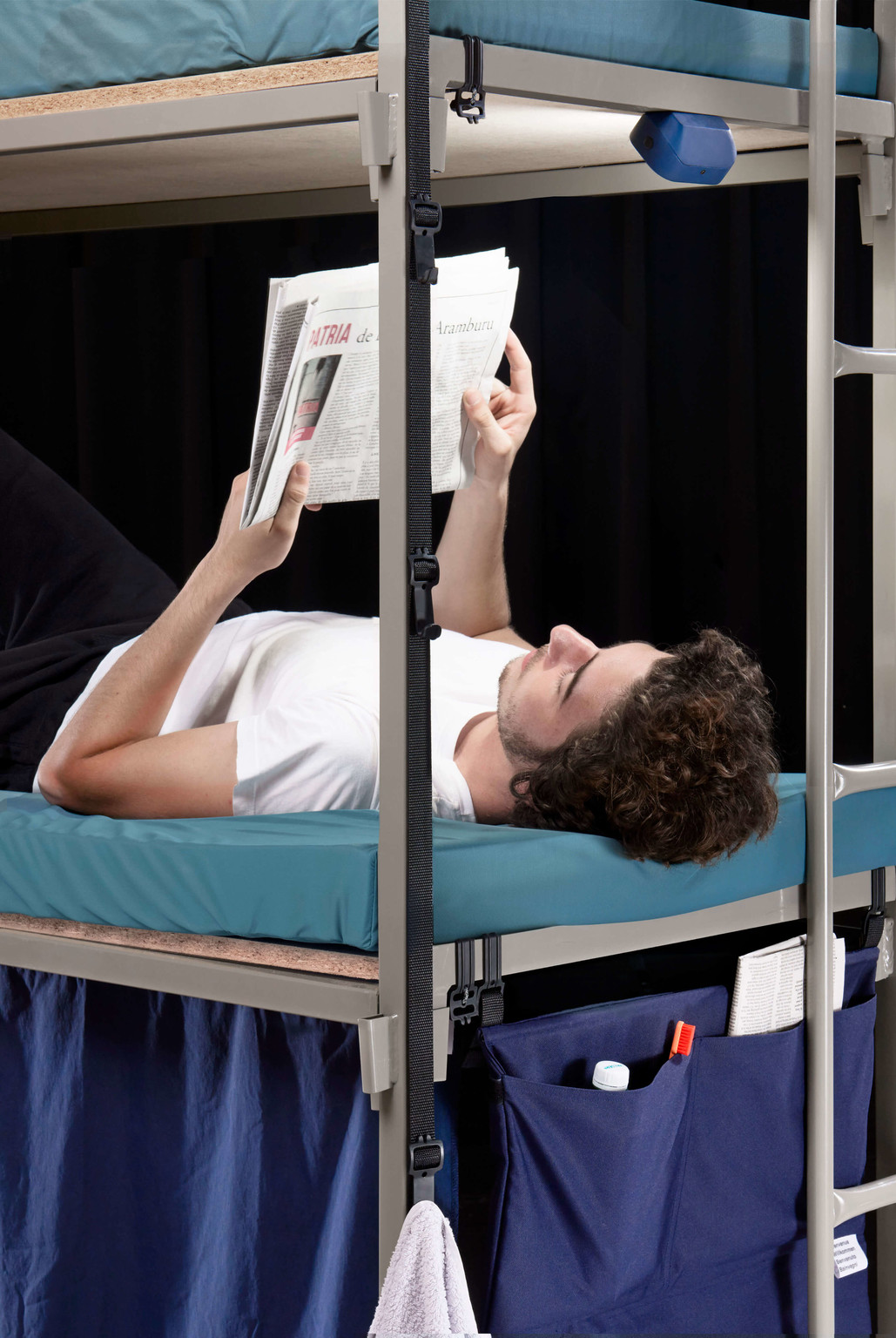

Looking at the typology of the nuclear shelter and its usage in Switzerland, mostly, as home to migrants and homeless people, Guetta drives a political point home in a skillfully crafted and sleek set of products. Titled Abri +, the project presents a set of objects — a lamp, a small bag, a curtain and some hooks — that seek to allow a customization and interaction with the limited space of the nuclear shelter bunk bed that allows for more privacy and a better sense of space. “This project tries to answer to an obvious necessity in a very standardised surrounding,” Guetta says. “It helps welcome the most needy people in a more human way.” Using simple devices, Guetta creates a simple and private environment, while creating awareness around the very real need — in Switzerland and elsewhere — to welcome others in a way that makes them feel welcome.

Projects such as these talk use ingrained ways of making and traditional design typologies to generate alternatives and possibilities, creating more complexity in times that are already convoluted. These projects go beyond the somewhat simplistic rhetoric of simple problem-solving in design, and are much more attuned to the contemporary. Nevertheless, their narratives are non-linear, which makes them harder to communicate. Contemporary narratives around design are still, in their majority, quite simple: they focus on formal details, crisp renderings, good product shots and sound bites that are easy to understand, process and regurgitate over countless blog posts, tweets, Facebook updates and listicles. This same clear reasoning, in a mid-century, post-war, Modernist context, allowed New York’s Museum of Modern Art to educate its audiences with the effectively titled ‘Good Design’ exhibition series (1950–55), showcasing the best of industrial products in semi-annual displays. In a similar way, it allowed IKEA to flat-pack and disseminate their particular philosophy for living around the globe. And, on another scale, the same linear narrative channels funds for utopian design projects such as John Habraken’s Heineken-supported WOBO bottle/brick.

“If design wants to grow and expand, and to be able to face those same problems, then it is not only the discipline that has to change, but also all the machine that feeds from it and depends upon it.”

As the field of design slowly breaks free from the industrial mindset that generated it, it also needs to find a new space and context. In the contemporary post-industrial Western world, it becomes clear that the simplistic narrative that could be applied to the ergonomics of a chair or the hinge of a door can no longer be applied to the kind of problems design ad designers are actively seeking to tackle. But if design wants to grow and expand, and to be able to face those same problems, then it is not only the discipline that has to change, but also all the machine that feeds from it and depends upon it — designers, studios, museums, companies, schools, research centers and so on. And with this understanding we will be able to shift boundaries and widen our scope of action, illuminating alternatives for this field, and allowing things to grow for themselves.

Vera Sacchetti (1983) is a design critic and curator, co-curator of TEOK Basel and co-founder of the editorial consultancy Superscript. She serves in a variety of curatorial, research and editorial roles, most recently as one half of the curatorial initiative Foreign Legion and associate curator of the 4th Istanbul Design Biennial — A School of Schools. Her writing has appeared in Disegno, Metropolis and The Avery Review, among others.